I was about fourteen the first time I was introduced to the concept of the shadow through Ursula le Guin’s

Earthsea Quartet, in which Ged split off a part of himself out of a foolish desire to prove himself and spent many years running from his shadow. Later, when I was sixteen, my counselor, Fiona (who was also practiced in Celtic shamanism) explained the shadow as all the parts of a person they don’t like – that they are afraid of – that they don’t want to deal with. She talked about bringing the shadow into the light of awareness and encouraged me to write a list of all the things in myself that fitted this description. It was easy to pinpoint external things: the things I felt guilty about, the obvious things I struggled with. It was harder to dig deeper than that, into the tangled unconscious web of depression and trauma that I wasn’t ready to face. I wanted to make things special and spiritual. I didn’t want to deal with the raw ugliness of reality.

The shadow is the realm of nightmares and the parts of psyche that are hard to face: pain/sadness, fear, rage, the horrific: too hot or too cold for comfort. A friend of mine who was who was practiced at lucid dreaming was warned never to try to meet his shadow. He took that as a challenge and so one dream, while he was flying along, he decided to do it. Suddenly a figure appeared, a

The shadow is the realm of nightmares and the parts of psyche that are hard to face: pain/sadness, fear, rage, the horrific: too hot or too cold for comfort. A friend of mine who was who was practiced at lucid dreaming was warned never to try to meet his shadow. He took that as a challenge and so one dream, while he was flying along, he decided to do it. Suddenly a figure appeared, a doppelganger

of himself, but darker, with a malicious grin. The dream abruptly morphed into his worst nightmare and my friend, an arachnophobe

, was being eaten by an enormous spider while his doppelganger

laughed.

The shadow is a terrifying concept, yet compelling. We might know there is something there but we don’t know what, and perhaps there is another level of

The shadow is a terrifying concept, yet compelling. We might know there is something there but we don’t know what, and perhaps there is another level of naivete, or several more layers, or hundreds. We will never know until we begin the arduous task of peeling them back. We may hope for specialness, for treasure, but that is unwise because it opens us up for unhinged delusions and losing our path.

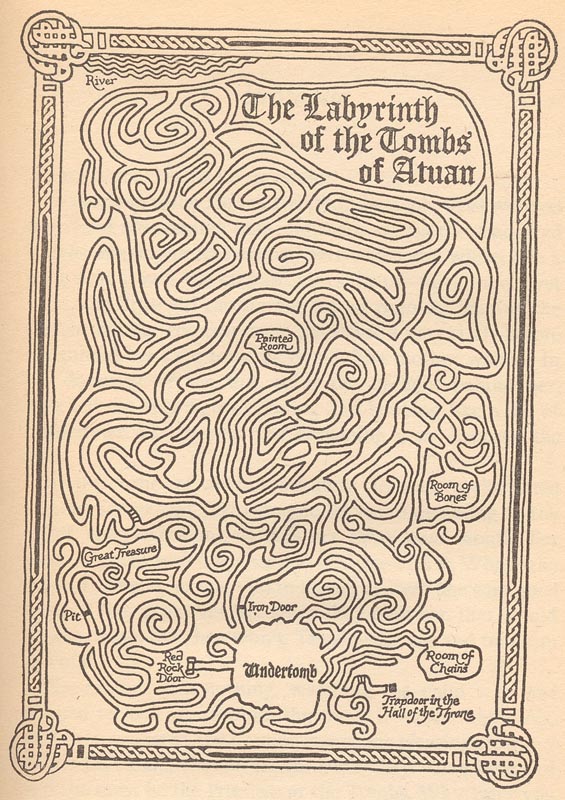

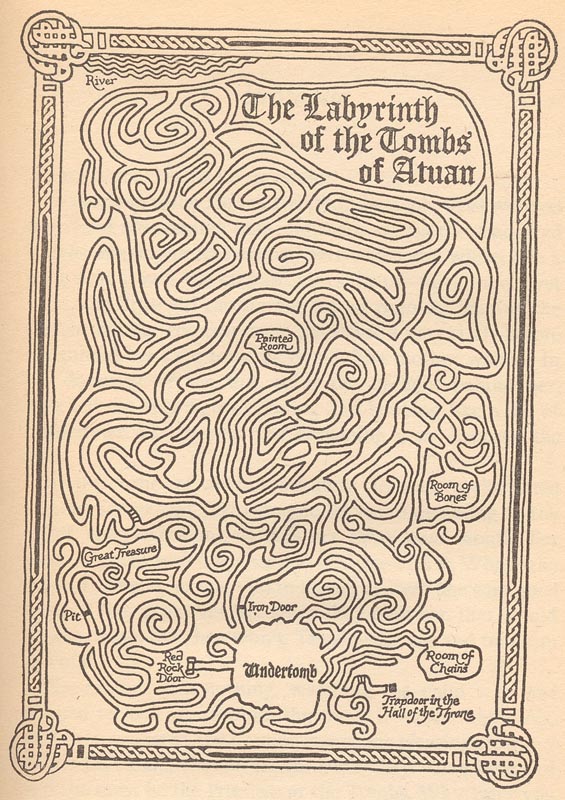

I think of shadow work as stumbling in the dark, like the le Guin’s priestess in her underground labyrinth, t

here is danger in rushing in: the danger of being lost to the blackness, of starving to death. We have to feel our way, to edge carefully around the walls until we learn the map. Then we can be at home in the dark landscape of unconsciousness. That is why the work is worth doing: because when you face the most terrifying parts of self, there is nothing left to fear and as if we can process these things in the light of consciousness, they don’t need to manifest externally.

I think of shadow work as stumbling in the dark, like the le Guin’s priestess in her underground labyrinth, there is danger in rushing in: the danger of being lost to the blackness, of starving to death. We have to feel our way, to edge carefully around the walls until we learn the map. Then we can be at home in the dark landscape of unconsciousness. That is why the work is worth doing: because when you face the most terrifying parts of self, there is nothing left to fear and as if we can process these things in the light of consciousness, they don’t need to manifest externally.

I think of shadow work as stumbling in the dark, like the le Guin’s priestess in her underground labyrinth, there is danger in rushing in: the danger of being lost to the blackness, of starving to death. We have to feel our way, to edge carefully around the walls until we learn the map. Then we can be at home in the dark landscape of unconsciousness. That is why the work is worth doing: because when you face the most terrifying parts of self, there is nothing left to fear and as if we can process these things in the light of consciousness, they don’t need to manifest externally.